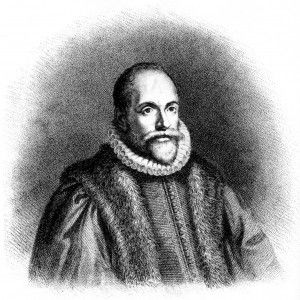

Recently Point Loma Nazarene University (or more precisely, its Wesleyan Center) hosted an academic conference entitled “Rethinking Arminius.” That would be Jacob Arminius (1559-1609), a Dutch theologian who is widely regarded today as the quintessential anti-Calvinist champion of human free will. Arminius is dear to Wesleyan and Nazarene folk, but the man himself was long ago replaced by a caricature, and the folks at Point Loma were out to set the record straight. The conference might just as well have been called “The Quest of the Historical Arminius.” To help with the quest, Point Loma called in some big academic guns from Princeton and Leiden (Netherlands) and elsewhere. The result was a high-caliber academic treat, and some surprising revelations.

About ten seminarians from Bethel San Diego attended, and learned a lot—not just about a 17th century theological controversy, but about the theological guild today, and how it goes about its business.

Perhaps one of the most significant insights of the conference was that the debate in which Arminius got so famously embroiled was an intramural debate among Reformed theologians. There were no outsiders; everyone involved was already inside the Calvinist tent. Arminius himself was at least ninety-four percent Reformed, and was never removed from his Calvinist chair or expunged from Reformed church membership. The man bled Geneva. In fact, his pushing of the envelope was arguably no more radical than some of the ideas more recently promoted by Karl Barth and Thomas Torrance, whose Reformed credentials have rarely been questioned.

Nevertheless, the Reformed Synod of Dort (the Netherlands) in 1618-19 drew a line in the sand, rejecting the free will views of their fellow Calvinist Jacob Arminius. But the basic disposition and sensibility Arminius represented has never gone away, and indeed never can as long as believers and seekers give epistemic weight to moral sensibility. There is something unacceptably dissonant between the heart of Jesus, weeping over wayward Jerusalem and longing to embrace them like a mother hen her chicks, and the image of a ruthless deity who wills the majority of the human race into eternal damnation before they are even born. Many will continue to believe that either we discover the heart of God supremely in the face of Jesus or we do not.

On the more whimsical side, we were reminded that a band of ardent Puritans, exiled from England, sojourned in Leiden for a time prior to their trans-Atlantic voyage to found New England and what became colonial America. We learned that their leader, John Robinson, himself no friend of Arminius, rented a home right across the street from his opponent.

But of equal significance to conference attenders was the manner in which academics engage in theological and historical dialogue today. The speakers and delegates were almost entirely white males. Women and minorities were conspicuously few. Discussion and debate was intellectually stimulating and impressively well-informed, but at times woefully deficient in social intelligence and basic empathy. But this is often the way it is at the American Academy of Religion too.

Point Loma Nazarene University deserves kudos for organizing this excellent event. The conference highlighted a number of useful sources for Arminius studies. Two are forthcoming in 2012: a biography of Jacob Arminius, Theologian of Grace (Oxford) by Keith Stanglin and Thomas McCall; and an annotated translation and introduction to Arminius and His “Declaration of Sentiments” (Baylor). Finally, there is Jeremy Bangs’ work on the Dutch segment of the Pilgrims’ peregrinations: Strangers and Pilgrims, Travellers and Sojourners: Leiden and the Foundations of the Plymouth Plantation (2009).

We are particularly interested in the perspectives of the Bethel students who attended. I invite those of you in this group to join in with your comments now, particularly your observations on the conference subject matter, the demographics of the participants, the ethos of the speeches and conversations, and perhaps also what you took away with respect to your own vocational aspirations. Other readers with opinions on Arminius are welcome to join in too.

6 Responses to Rehabilitating Jacob Arminius